The following is an excerpt from a book on stream

fly fishing for trout currently being written by Michael Gorman.

Fly Fishing Equipment Basics

by Michael Gorman

The

Hamm’s Beer Commercial The

Hamm’s Beer Commercial

“From The Land of Sky Blue Wa-a-a-ters comes the beer refreshing . . . Hamms,

the beer refreshing. Hamms!” This commercial refrain was sung on television

when I was a kid. The tune was cleverly catchy, but what drew my intense

attention was the scene of a fly angler standing in the middle of a beautiful

mountain stream casting a fly rod as the beer is advertised. When the line is

extended on the final forward stroke the fly lands immediately in front of the

camera lens held at water level. The artificial drifts a short distance when

suddenly a trout charges through the surface to grab the fly. To a young fish

killer this was an exciting moment. My very favorite commercial. I always

watched it with high anticipation. The trout always got the fly. Someday

I would be that fly fisherman.

My moment to graduate to a higher level of fishing consciousness soon arrived.

In the summer of my fourteenth year I pedaled my Schwinn American --- ruby red,

and very fast --- to my local sporting goods store. Summer work had allowed me

to set aside enough cash to buy a fly fishing outfit and some flies.

As for research, I had done none. A couple of my

uncles had talked about having done some fly fishing in their younger years, but

neither had ever demonstrated their skills. Besides, each had lost his religion

to consort with a spinning rod.

My local library was of little

help. It had but one fly fishing text which centered on fly fishing for

steelhead. The book went home with me for a brief stay. I was a trout

fisherman. There was little which was helpful I could glean from the text to guide me in

the selection of fly fishing gear to suit my needs. So, the book was soon

returned to the Stayton Public Library. There was no chance I would be billed

at the rate of ten cents a day for an overdue text.

As I strolled the main aisle

of my local sporting establishment to buy my first fly rod I, naturally,

examined the price tags. Assuming all fly rods are essentially created equal, I

chose the least expensive of the lot. Fly reel --- same thought process and

selection. I got a real deal on the fly line: 98 cents. I already had

thousands of yards of monofilament at home, so there was no need to buy a leader

since I had no suspicion that a leader should be tapered. Ah, now to the flies.

I made a studied perusal of

the fly bins, and then politely asked for suggestions. My hope was that the

patterns that held some visual appeal for me would be confirmed by the store

owner. Nope, didn’t happen. He suggested an assortment of drab looking fur and

feather concoctions. Even tried to sell me a fly he had tied using some of his

young son’s hair in the wing. Maybe not

coincidentally, the boy had been named after a fish: Marlin. So, after thanking

him for his suggestions I pro ceeded

to select a handful of artificials that suited my taste. The sole criterion was

that the fly be pretty. I was particularly fond of flies that had red floss somewhere on

the body. Among my other feathered dandies, the Royal Coachman was the runaway

winner in the “pretty” category. ceeded

to select a handful of artificials that suited my taste. The sole criterion was

that the fly be pretty. I was particularly fond of flies that had red floss somewhere on

the body. Among my other feathered dandies, the Royal Coachman was the runaway

winner in the “pretty” category.

After paying for my collection of items, I inquired about the

basics of fly casting and fly fishing technique. The shop owner queried “Do you

know how to fish a salmon egg on a spinning rod?” Little did he know of my

angling prowess. I humbly replied,

“Yes.” To my relieved amazement he finished with “Well, you a fish a fly the

same way you would a salmon egg.” Fly

fishing was going to be fun . . . and easy.

Is

it “bird nest, or “bird’s nest”?

After a hasty

assemblage of my new fly fishing outfit at home, it was time to practice casting

in the backyard. Back & forth, back & forth, let it rip. Forth & back, forth &

back & forth, let it rip harder. Next time: FASTER, HARDER. My initial fly

casting attempts were as successful as training a cat. The more enthusiastic my

efforts, the more disastrous the results. Line, leader and fly would fall

together in a tangled nest a few feet beyond my rod tip. Sometimes it was just

line and leader. A whip-cracking sound was often accompanied by the

disappearance of the fly once tied on the end. I whirling lawnmower blade would

eventually find it, but I would not.

Then an interesting thing happened. As my casting arm grew

weary and weaker the better my casts became. They graduated from grossly

pathetic to merely bad. Then, from bad to poor. I was making progress.

Lighten up on the power, shorten the arc of the waving rod tip, and the line

would sometimes land fairly straight without tangling. Hope emerged.

The next ten years found me vacillating somewhere between

exhilaration and throwing the fly rod javelin into the trees. Often I parked

the fly rod in the closet and took my dependable Old Friend, the spinning rod,

on my angling adventures. Sometimes the fly gear did not see the light of day

for months, even during the prime of the fishing season. It was a fickle

affair. My casting ability leveled off at mediocre, and my fish-catching

results were inconsistent. I blamed these on my lack of fly fishing athleticism

and my inability to find the one, true Magic Fly. Not once did I suspect that I

might have mismatched my rod, reel and line combination, or purchased inferior

equipment unable to perform well under ANY circumstances.

It wasn’t until graduate

school at OSU that I met another fly angler. His experience far exceeded mine,

and he talked a good game. We agreed to fish the Middle Deschutes in late

spring, in pursuit of brown trout and rainbows.

Fishing was slow but we

each brought a couple of brown trout to net. During a mid day break my new

friend asked if I wanted to cast his rod. I readily accepted. In spite of my

ability his rod cast the line effortlessly, extending it smoothly both fore and

aft. When I presented the fly on the final forward cast it settled gently on

the water at a surprising distance from us. Subsequent casts produced the same

results. I COULD cast a fly. My companion explained to me in simple terms that

a fly rod and fly line are meant to be a “matched pair”, and that a fly line

should be tapered in order to extend its length upon being properly cast. This

was all new to me, and made good sense. I reflect on this as a pivotal day in

my fly fishing life. When the student is ready, the teacher will EVENTUALLY

appear. This student had been waiting for more than ten years!

Purchasing a new fly rod

and line to match moved to the top of my outdoor priority list. And, in short

order, I followed through. I had a custom-built 8 ½’ Fenwick fiberglass made

for me. Upon my request I was allowed to watch the craftsman at work. I

learned the basics, and would eventually make some of my own rods.

My old Pflueger reel did an

adequate job of holding my new Cortland tapered floating fly line. With

a tapered leader rounding out my new outfit I was ready to begin fishing

life anew.

An evolutionary chain

reaction was begun. New balance, functional equipment allowed my casting skills

to blossom. My confidence soared, which, then, fed my persistence. Persistence

led me to increased fish-catching success. Success led to more success.

Critical mass had been reached.

I said goodbye to my

long-time girlfriend – Old Blue, the spinning rod --- and took up with a new

love. If you have ever experienced the new frontiers of love and white-hot

passion you can relate to my emotional state. If you can’t relate, oh well.

This passion would lead me eventually to make fly fishing the center of my

life’s work. It would not be a straight line path. You will see as the pages

which follow are turned.

Adequate equipment can make

or break the angler in the early stages of the pursuit. There are fly fishing

tools, and there are fly fishing toys. Toys are the $39.99 “just add water”

outfits that make enjoyable and productive fly fishing very unlikely. Major

league hitters don’t use a Little League bat. Tiger Woods doesn’t buy his golf

clubs at the pawn shop. And, you won’t find many Yugo’s driven in a NASCAR

race. Use tools, not toys.

Equipment Basics

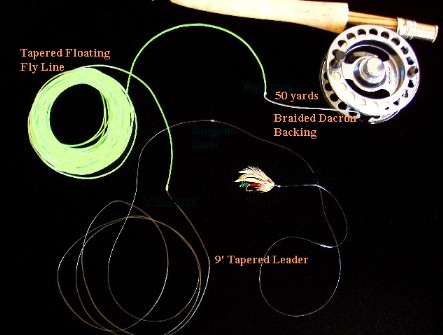

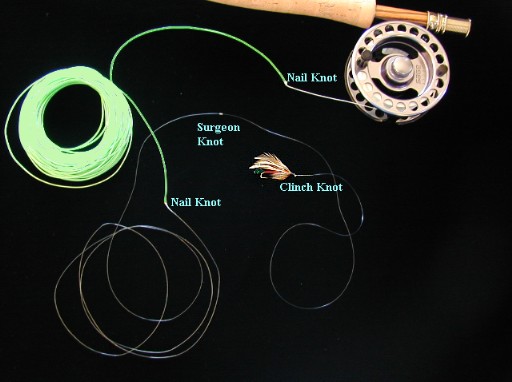

The basic fly fishing

equipment system is composed of a fly rod and a reel holding the fly line.

Behind the fly line, secured to both reel arbor and tied to the rear of the

line, is 50 – 100 yards of braided Dacron backing. A leader, commonly 9’, is

attached to the front end of the fly line. At the unattached fine end of

the leader a fly is tied. Add water and fish.

Rod Selection --- Know

Thyself

As explained in the Introduction, as a teenager

beginning my fly fishing career I had no clue there were any major differences

among fly rods other than that some were longer or shorter, thinner or fatter,

different colors, different prices. It did not occur to me that there

might be

specific fly rods for specific gamefish. No clue that the same fly rod for

pursuing bluegill might not be the same rod for fighting blue marlin.

Commit to be a specialist as you

start. Focus on what fish you will initially try to catch on a fly. Crappie,

bluegill, perch, small bass, small trout? Trout of all sizes? Steelhead? All

sizes of bass? Salmon? Saltwater gamefish?

Time for the first of a couple

analogies. Though I am a hunter --- a hunter of fish --- I am not hunter who

uses a gun or rifle. However, I have a rudimentary understanding of different

weapons for different quarry. Upland game bird hunters use a shotgun which

sprays a high-speed rain of small buckshot for quail, chukars, and pheasants.

Deer and elk hunters use a high-powered rifle that shoots a single bullet accurately

at great distance to bring down a large animal. Large, at least, compared

to the aforementioned birds. A hunter is called in on a humanitarian mission

to dispatch a rogue elephant, weighing several tons, that is trampling African

villagers. He will use a rifle that fires a monstrous caliber slug.

Now, the elephant rifle could be

used to hunt a hapless quail, but little would remain for dining purposes.

Conversely, a standard shotgun blast using a conventional shotgun shell will do

little, if anything, from a hundred yards to a deer or elk. Even at close

range, a shotgun assault on an elephant will probably guarantee that the shooter

becomes a flattened statistic.

Until the rules are changed whereby

golfers must run after their golf ball, then do ten pushups before the

next shot, the game holds little fascination for me. But I do understand this

game where physical conditioning is totally optional, where weaklings and the

flabby can ride in carts to pursue their slices and hooks all day with little

corporeal challenge. Here comes the analogy I promised.

A golfer carries a bag of clubs. There are wood

drivers, an assortment of irons, a wedge or two, and a putter. Imagine

using a single club to play an entire 490-yard, par 5 hole. Let’s select a

putter. Instead of driving the ball 250 yards off the tee, you manage 50.

Now, envision a few problems with the

putter in the rough, in the sand traps, and attempting to loft a long shot over

the water hazard. Get the idea?

Over many years of running a fly

fishing shop I encountered would-be fly fishermen (a gender-general term

hereafter) who wanted me to help them select an all-purpose rod designed to

catch anything that swims. A tool for enjoying small fry from the farm pond, to

bruiser chinook salmon that might top 40 pounds. No such rifle. No such golf

club. No such fly rod.

Fly rods can be found in lengths

generally ranging from 6’ to 15’. Look hard enough you can find probably find

ones even shorter and even longer. There is no direct correlation between a

rod’s length and the species that it can handle. A 15’ two-handed spey fly rod

is not intended for pursuit of a 500 pound billfish. It is best suited for

salmon and steelhead that may range, typically, from 6 to 25 pounds. The length

of a general-use saltwater big game rod is around 9’. You might also select a

different 9’ rod that is perfectly suited for small trout and panfish.

Here’s how to envision the difference. Think of a willow branch and a billiards cue stick of the

same length with line guides on them.

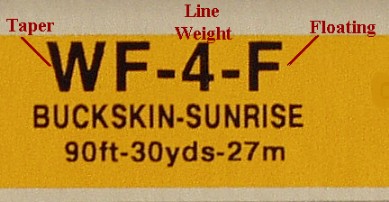

The best clue you have about

the targeted intent of a quality fly rod built in the 1970’s up to the present

is written on it. If you examine the portion of the rod just above the

cork grip (“handle”), an inscription there will indicate either blatantly, or in

an easily deciphered code, the intended fly line “weight” to be used on the rod. This will be the

fly line that causes the rod to bend properly as it extends the fly line fully

and gently upon the water.

Fly line “weights” range from 0 to

14. What follows is a chart and the “most appropriate” gamefish typically

sought:

0 - 3-weight line/rod

panfish, small trout

4 - 6-weight

line/rod trout, summer steelhead

7 - 9-weight

line/rod bass, steelhead, salmon, bonefish, smaller saltwater

species

10-weight

line/rod heavy salmon, saltwater

11 - 14-weight line/rod tarpon,

large saltwater fish often exceeding 100 lb.

If you anticipate a

question you may be asked during the world championship Trivial Pursuit

competition about the actual physical weight of a give fly line “weight”,

or you just want to know in order to dazzle your friends at a party, here goes.

As fly fishing equipment

evolves, standards may be slightly adjusted. So, know that the numbers cited

here may change (or have changed) as a result, and are, therefore,

generalizations. Only the tapered portion --- typically 30’ – 40’ --- of a fly

line is weighed to determine the designated weight of a fly line. The actual

weight measurement is calculated in grains. 437 ½ grains = 1 ounce. A partial

table follows.

Line weight number Weight

range (grains) Rounded Average (grains)

1

54 - 66 60

2

74 - 86 80

3

94 - 106 100

4

114 - 126 120

5

134 - 136 140

6

152 - 168 160

7 177 – 193 185

8 202 – 218

210

Rather boring stuff, but

now you know. Let’s move on.

Most fly anglers fish

streams, and usually for trout. Unless you are going to be a BIG trout

specialist, in pursuit of the occasional summer steelhead, a 9’ 5-weight rod is

considered the best all-purpose combination by most of several thousand fly

anglers I’ve dealt with selling fly rods for 20 years. If you intend to be

a small stream / small fish specialist, an 8’ to 9’ 4-weight rod is pleasant.

Even a small fish will put a lively bend in a 4-weight. A 9’ 6-weight is

an excellent choice if summer steelhead are part of your fishing mix, even

though trout are your main focus.

Why a 5-weight? A

4-weight rod does not perform as well in the wind, nor does it handle weighted

flies or long casts as well as a 5-weight. A small trout, which we all

catch in most streams, has to pull very hard against a 6-weight to impress you

with his fight. Fishing a light leader with a small fly on a heavier rod,

the angler is more likely to break off a fish on the strike or during the fight.

A hook-set with a more powerful rod generally translates into a more powerful

impact on leader and fly. Too, a larger diameter fly line may dictate a

bit larger, heavier reel for your six-weight system. It won’t be as

feathery light as a 4- or 5-weight.

Some anglers are enamored with the

thought of landing a large fish on an extremely light (“ultralight” is the word

commonly used, especially by my spinning rod brethren) rod/reel/line

combination. Can it be done? Yes. Can it be great fun? Yes. Can it do harm

to the fish, even kill it under the right conditions? Yes.

Time for a little science. As water

warms it is less able to hold dissolved oxygen. Fish, like us, need oxygen. It

is extracted from the water and introduced into the fish’s bloodstream as the

water passes through the gills. If the water is dangerously warm --- let’s say

68 – 75 Fahrenheit degrees for a stream trout --- a fish played for a long time

after initially being hooked can get so exhausted it will be unable to recover,

unable to extract enough dissolved oxygen from the water quickly enough to

survive. Imagine someone threatening to shoot your dog unless you consent to

run a marathon at an elevation equivalent to that of Mt. Everest. You’re gonna

die! So, a rod matched to the size of the fish being sought, makes good sense.

If the water is warm in late summer and fall, play your fish quickly --- within

reason --- to minimize its exhaustion. An ultralight rod, because you usually

cannot exert as much forceful tension on the fish, may overtax and kill it.

Not all fly rods are created

equal. Some definitely have better pedigrees, and for that reason perform

better, look nicer and cost more. You will find graphite fly rods ranging

in price from $29.95 to more than $700. What’s right for you?

First of all I want you to dispel a

very common, and virulent, line of logic from your thinking. So often I’ve

heard novices say something like, “I’ll get a cheap rod to get started with /

learn with, and then move up to good equipment.” This is totally backwards.

Someone with minimal skills and experience needs a better tool, not a

poor one, a toy. Assuming it is matched with an appropriate fly line, a good

rod will encourage and accelerate your learning. Casting will be fun and easy

once you have a little casting instruction. Your line and leader won’t always

land in a heap. Learn from my mistakes!

Realistically establish your

rod budget. My suggested minimum --- take it for what it’s worth --- is

$100. Is it better to buy an inferior rod and struggle as I did to make it

work? You may not be able to overcome the discouragement, soon giving up

on the sport. Or, it may mean you will have wasted your initial investment

and have to buy the good rod you should have bought in the first place.

Wait, if necessary, until you save up the needed cash. You only have to

buy the right rod once.

Get a reputable brand name rod, and the best you can afford.

If you can’t cast it first, don’t buy it. Ask about a guarantee.

Some rods have them, and some do not. You will pay more for a rod with a

no-fault breakage warranty, but it can be well worth it. Some careless or

unlucky anglers break a rod every year. They need a guarantee. 90

days or one year is not enough. Get a minimum 25-year guarantee.

Lifetime is better.

Choices, choices, and more

choices. When I first took up downhill skiing I did not have a very good

idea about what skis I should by. Every salesperson had their suggestions,

and there was no recurring theme. So the first few times I went skiing I

rented skis . . . and watched. I watched the better skiers. In

particular I looked at the brand names on their skis. A small handful of

names predominated. My choices were narrowed and I purchased some good

skis that have served me well.

You can do the same basic detective

work with fly rods, or any other piece of fly fishing equipment for that

matter. Whether in a fishing store or along a stream, ask veteran skilled

anglers what they use. The more sources you consult the greater the odds you

will see several brand names rise to the top. Know that any given rod

manufacturing company has a variety of rod models at a variety of price points.

Going into the car dealership and you would not say, “I want a black Ford with

air conditioning.” You specify Thunderbird convertible. The same is true for

ACME fly rods. Specify the Graphite III Trout Turbo series.

Novices are shy about casting in

public. They also reason that they could not distinguish one rod from

another. I disagree. Insisting the angler should cast a variety of rods ---

same length, same line weight --- side by side, I have found to always be

enlightening for the caster. Besides giving them a mini casting lesson ---

which they always appreciated --- the rookie could get a “feel” for any given

rod, even if the casting technique was poor. The particular unique timing of

the rod bend, the lightness or heaviness of the rod, the shape and comfort of

the cork grip, even an appreciation or dislike of the rods aesthetics all served

to give input to the wannabe fly angler. If one particular rod above all others

evoked a smile from the caster, the case was closed. That’s why I insist

everyone, in spite of skill level, should cast a variety of rods before the

final decision. This is accepted protocol at better fly shops and sporting goods

stores.

Math time. A simple test that

should be passed by all quality fly rods: the number of guides, not counting the

tip top, should equal a number one more than the whole number of feet in the

rod’s length. For example, a 9’ rod should have a minimum of 10 guides. An 8’

or 8 ½’ (drop the fraction) rod should have a minimum of 9 guides. Inferior

brands usually violate this simple rule of thumb. It costs them more in time

and money to get it right. Count the guides!

EVERY fly fishing rookie I have ever

encountered hails the myth that all bamboo rods are special and valuable.

Hundreds of times I’ve heard from the smilingly proud purchaser: “ I found this

at a garage sale. I only paid $4 for it! What do you think it’s worth?” After

I examine the vintage stick that most likely has a crooked tip, guides that are

rough with corrosion, and too small for modern fly lines, I do my best to avoid

a direct response to the “How much is it worth?” question. Instead I talk a

little about art, specifically great painters Rembrandt, Monet’, Picasso, et

al. Anyone with a brush can paint on canvas or paper. The signature of an

acknowledged talent on a painting can add great value to a technically fine

piece of art. In the same way, a fine bamboo rod will bear the signature of a

great rod building craftsman. If it does not then the tool most likely does not

have great monetary value, and is probably not a great fishing tool. I phrase

all this in such a way as not to hurt the feelings of the rod owner. Then, I

test their resolve. In an upbeat manner, I tell them what must be done to

renovate the rod to fashion it into a quasi-functional fishing tool. When I

suggest to the owner that he will have to strip and refinish the blank, then

replace and, possibly, relocate the guides, they start to understand that the

rods 50 and 60 years past are rarely the best choices to fish in light of modern

tools. Most eventually acquire a graphite rod, and will fish more effectively

for doing so.

Fly Lines

--- Land of Confusion

My first fly line cost

98 cents: a forest green piece of string that always landed in a heap when I

cast it, unless I had a strong tailwind. It took me years to discover that most

fly lines are tapered. How are you with some of the basic principles of

physics? When a tapered line is properly cast, the transfer of momentum

(p = mv) is passed smoothly along the length of the fly line causing it to

unfurl on the final forward cast. The line lays out fully extended on the

water. As you might now suspect, mine was of the taperless variety. (mv +

taperless fly line = a coiled mess = lousy presentation of the fly +

frustration)

To keep it simple, there are essentially two fly line tapers: double taper and

weight forward. Most of my beginning students have heard of the double

tapered fly line. Those who have purchased a line with little or no

knowledgeable counsel have purchased a double tapered fly line. This, most

likely, is not the best choice for a fly

angler’s first line, though it is a quantum leap better than my initial purchase

with no taper.

A

double taper fly line is, typically, 82 to 90 feet long. As

the name would imply, the line gradually decreases in diameter over a length of

about 30 feet at each end. The midsection, or belly, is about 25 to 30

feet long.

Assuming the line is

cast with some modicum of skill, here are the advantages of a double taper:

1.

The line and fly are presented very softly, delicately upon the water.

Minimum disturbance to the trout caused by line splash. If a dry fly is being

used, a delicate presentation decreases the possibility of a hard landing that

might sink the fly upon impact.

2.

The double taper is an excellent choice for roll casting. A roll

cast is used when the angler has a high bank, high grass, bushes, or trees to

his or her immediate rear. With a standard back cast, the caster risks breaking

off the fly. A roll cast alleviates the problem as the fly line passes barely

to the rear of the angler during the presentation. More on casting in a later

chapter.

3.

Economy. Because the double tapered line is tapered at both ends,

when the fishing end of the line has cracked and no longer floats (assuming it

is a floating line), merely pull the line off the reel and turn the line around,

re-attaching it to the backing, to fish the un-used tapered end.

Now, let’s contrast this

with the weight forward taper design.

=====================================

Advantages of the weight forward taper:

1.

Distance casting. Though most fishing in streams and rivers is done at

close range --- 25 – 40 feet --- there are times that a longer cast must be made

to reach the fish. To increase the casting distance, the caster strips loose

coils of line from the reel which fall to the water or ground at the fisherman’s

feet. During the forward casting motion, the angler allows this coil, or coils,

of fly line to “shoot” through the rod guides in order to extend the cast. As

the slack line “shoots” (travels with velocity) through the rod guides there is

naturally friction between the line and guides. The less the friction the

farther the line carries to extend the cast. Because the running line portion

of the weight forward line has a relatively small diameter compared to

the mid-section, or “belly”, of a double tapered line, there is less friction.

This results in a longer cast with less effort.

2.

Casting into a breeze is a common occurrence in fly fishing. The weight

forward design is better able to pierce the wind and present the fly than the

double tapered line.

3.

Sooner or later the well-rounded stream angler is going to cast heavily

weighted nymphs or wet flies, and bushy air-resistant dry flies. Moving the

momentum of the cast along the full length of extended line and leader so that

the whole system rolls out in a fairly straight line presentation is best

accomplished with the weight forward design.

4.

Most beginners naturally start their casting practice and fishing at

short distance, inside 30’. A weight forward line “loads” (bends) the rod

tipper quicker at short distance than a double taper. It is the bend of the rod

that propels the fly line. Most anglers will agree that very short line casts

are more easily accomplished with the weight forward taper.

5.

The weight forward taper, though not quite as good as the double taper in

these regards, does a quite passable job of roll casting a fly, and can present

a fly with reasonable delicacy when required to do so.

For fly anglers seek

maximum opportunities --- short casts / long casts, big fly / little fly,

casting in the wind, reasonable capability of roll casting and delicate

presentation when necessary ---- the weight forward line is the better choice.

The double taper, though economical from the standpoint of being able to reverse

the line after wearing out one end, is more of a specialty line. This is

particularly true and important for the beginning or occasional angler.

There are fly lines that float.

There are fly lines that sink. There are fly lines that have a portion that

floats and a portion that sinks.

The sinking fly line has a specific

sink rate, ranging generally from 1 to 10 inches per second, or “ips”.

Fly lines also come in a variety of

colors. Floating lines are the most exciting. You can choose from muted olive

and tan to yellow, orange, vibrant green and fluorescent red. I love and use

colorful floating fly lines. This always leads to the question “Can fish

see color?” The answer: “They most certainly can.” Do they see red as we see

red, or blue as we see blue? I don’t know, but they can distinguish one

color from another. Just ask any experienced fly fisher who has presented a fly

to selective trout. The correct color can be the difference between success and

failure.

“Do brightly colored fly lines scare

the fish?” I am often asked. I believe it is the splash and shadow of a hi-vis

fly line that disturbs the fish, rarely the color. I would certainly get

rousing disagreement from some anglers on this point, especially from my friends

in New Zealand who are positively phobic about colorful fly lines. The Kiwis

insist that their trout are so wary that only a subtle olive, tan or brown fly

line should be used to fool them. Unfortunately, having fished more than a

dozen rivers there --- most multiple times --- on both the north and south

islands I have enjoyed great success in New Zealand with my gaudy fly lines, to

the gasping consternation of the Kiwi angling guides I have employed. The

stealthy approach, the angle and delicacy of the cast, and the appropriate

leader are of major importance. Fly line color is of little or no importance to

me with, perhaps, one very occasional exception. The trout are holding in flat,

shallow clear water. Circumstances dictate I must approach the trout from the

upstream position (fish hold facing upstream into the current). A dull colored

fly line makes sense if I am standing in bright sun and my

backdrop, as viewed by the fish, is in deep shadow. Besides me and my waving

casting arm being very visible, my fly line would be, too. That’s why you see

eye-catching photos of fly casting with the caster in the bright sun against a

darkly shadowed background. Maximum visibility.

For me being able to easily see my

fly line, even in dim light conditions, allows me to track my fly or its

proximity. Knowing the location of my fly allows for an accurate presentation.

While fishing, good visibility gives me the chance to react quickly to set the

hook, even when the take is very subtle. Sometimes the only indication a fish

has intercepted my fly is a very subtle hesitation or straightening at the tip

of the fly line. Lively colored lines make it easier for me to see such strikes

so I catch more fish. Any minor disadvantage here, in my mind, is greatly

outweighed by the plethora of plusses.

If you are going to have only one

line for fishing streams make it a weight forward floating line. Whether my

clients or I are fishing dry flies, wet flies in the mid-water column, or nymphs

along the stream bottom a floating line tops all other choices. Choose a color

that appeals to you in light of what I have written above.

Reels

--- The Good, the Bad, and the Mediocre

Having taught fly fishing classes

for more than twenty years I hear some misconceptions over and over from

students. Some ideas I hear so often that they attain status as Common Fly

Fishing Myths. One of the Top 40 Common Fly Fishing Myths of All Time is that a

fly reel serves little more function than to store the fly line. It’s held in

low regard as a passive piece of equipment being little-involved in the catching

of fish. Wrong!

If one of your fly fishing goals is to never catch a stream trout over 12” then

perhaps you don’t need a good fly reel. However, I

am going to make the bold assumption that few anglers --- including you ---

don’t list this as one of your objectives. It is rare to discover

fishermen who have a disdain for larger fish, so on the certainty that you will

eventually encounter one on the end of your line get a good fly reel

to best insure you will land such a fish.

I do not recall ever witnessing

someone, myself included, losing a fish because the fly rod failed to perform as

it should during the fight. Beyond “pilot error” the leading cause of lost fish

in my experience is due to the malfunction or inadequacies of the fly reel. A

large trout (14” or more) swimming hard downstream with the current at its back

can pull fly line from a reel at a startling rate. If you should hook a trophy

trout, steelhead, or salmon the speed at which the line disappears from the reel

is now classified as “frightening”. If the line is not released smoothly,

and with adequate resistance (drag), the odds favor the fish escaping.

If not a scofflaw, you have auto

insurance. You probably have homeowner’s insurance, medical insurance, and life

insurance. Unless you are a scam artist you rarely use your insurance, perhaps

going years without filing a claim. If you crash your car when you have a heart

attack as you watched your home burn down you are glad that you have insurance.

The same analogy applies to a good fly reel. You may not need to call on its

full capabilities often, but its reliability is there when you need it. The

reel is part of your fly fishing insurance team.

Here are a few fly reel

suggestions.

Get a quality brand name

reel. Be careful here because well-known spinning reel and level wind reel

companies may build lousy fly reels. I suggest companies that specialize in

fly fishing gear. A fly shop would usually be a better scouting location

then a general sporting good store. Think of physicians who deal with specific

ailments. A family practitioner should not be your choice for heart surgery.

Deal with a specialist. That way you will only have to buy your fly reel once.

A smooth drag is extremely

important. There are a variety of designs. The spring-and-pawl and disc drag

models are the two most common.

During the proper function of a

spring-and-pawl reel, a triangular “tooth” (pawl) works against a gear on the

inside of the reel spool. The pawl’s backside lays against a linear spring.

Most reels of this type have an adjustable drag knob so that tension on the

spring may be increased or decreased, increasing or decreasing the amount of

drag. The spring-and-pawl drag has a relatively small tension range. With

inferior reels the range soon becomes even smaller as the spring weakens. Too

often springs break and pawls wear out. Replacement parts are a hassle. Some

reel makers include an extra spring and pawl when you purchase their reel. I

don’t know if this is thoughtful service or an admission of the reel’s fate. I

lean to the latter. As evidence I no longer own any spring-and-pawl drag reels.

However, my personal choices aside,

there are some adequate spring-and-pawl drags. For financial or other reasons

you may be fishing with a reel of this type. If you run the risk of hooking a

large fish in moving water perform this simple test. Set the drag to maximum

tension. Assuming the reel is loaded with fly line, grab the loose end of the

line and give a hard, quick yank to simulate a fish running away at high speed.

If you end up with a tangled bird's nest as the spinning spool “overruns” the line

then you have seen the future. The tangled line will jam, and your fish will

instantly break off. Another possibility is that the pawl will disengage from

the center gear. Yikes! However, if your reel passes this test it bodes well

for encounters with big fish.

The majority of fly reels have an

exposed spool rim. As the spool turns you can assist the reel’s drag by

lightly touching the outer portion of the spool with your finger or palm. Those

anglers with an inadequate drag are motivated to learn this quickly.

A disc-drag reel makes good sense

and a good investment for most fly anglers I encounter. In the simplest terms,

a disc drag is a system where two precisely machined surfaces lay flat against

each other. As line is pulled from the reel spool one circular surface --- the

disc --- turns against the smooth resistance of the stationary surface which

faces it. A drag knob allows the angler to increase or decrease the degree of

friction between the two surfaces. Tension can be increased to the breaking

point on most models, or decreased to a bare minimum. The right setting, of

course, is found somewhere in between. Taking into consideration the fish, the

flies, the breaking strength of the leader, and the skill of the fisherman, the

broad setting range of the disc drag reel is a highly desirable feature. As

competition in the market place grows there is a corresponding increase in the

number of quality, budget-priced disc drag reels available.

On any good reel it is nice to be

able to switch the direction of the drag. This allows you to retrieve line onto

the reel with the hand of your choice.

Here’s another Top 40 Common Fly

Fishing Myth: better fly anglers retrieve line by turning the reel spool with

their casting hand. A right-handed caster, for example, turns the reel handle

with his or her right hand. Once a fish is hooked the angler switches the rod

to the non-casting hand to fight the fish. You don’t have to do this, even

though Grandpa did!

Let’s talk about the origin of this

myth by going to Europe. I choose to lay most of the blame on the English since

they comprised most of the early settlers of America and, naturally, influenced

our traditional angling methods. Hundreds of years ago in Europe the wealthy

and royalty owned the good land, streams and rivers included. If you --- a

commoner --- caught a fish or killed a deer you were poaching. We all remember

Robin Hood poaching the King’s deer in Sherwood Forest.

When not hunting with hounds for

other game, the chosen sporting method for angling was fly fishing. Now it

seems the Brits, once a fish was hooked, chose to retrieve the line and fish by

stripping/pulling in the line by hand. They did not retrieve line onto the

reel, letting the line fall in loose coils at their feet. The last statistic I

read about dominant digits indicated that 93% of our global inhabitants are right-handed, so the great

majority of these anglers cast and held the rod in their right hands. The line

was, therefore, stripped/retrieved with the left hand. Common sense would

dictate that the reel handle was naturally on the left side of the reel. The

right hand is busy holding the rod.

Now, envision this. A bigger,

stronger fish being hooked and played by a Line Stripper may struggle mightily,

pulling hard on the line. If the angler does not give back some of the line the

tension may break off the fly. The angler attempts to smoothly release line

through his fingers letting the fish run. If you have ever done this you know

things can happen quickly. Loose coils of lines can tangle or get caught on

something as the fish reclaims the slack line, running away at high speed. As the

right-handed angler guided and released the line with the left hand on

the left side of the reel, one of the potential line-grabbing problems

was the reel handle. There was always a chance that a loose coil of line being

pulled by a fighting fish could inadvertently be wrapped around the handle.

Simple solution: put the handle on the right side of the reel so it is out of

the way, one less hazard to catch the line.

Even as we enter the 21st

century it is not uncommon that fly anglers switch the rod to the opposite hand

to retrieve line as they fight a fish. They were taught this way and will teach

their young the same. Risking controversy, I would wager most do not know why.

Reminds me of a story

. . . A young

housewife, preparing a holiday dinner, cut a few inches off the narrow end of a

whole, uncooked ham. She placed the ham in the roasting pan, then put it in the

oven to bake. Her daughter, watching the preparation, inquired as to why her

mother had cut off the end of the ham. Mom replied she did so because her

mother (the little girl’s grandmother) had always done so. Grandma, overhearing

the conversation, revealed to Mom that the only reason she had cut off the ham

end prior to cooking was because it would not otherwise fit into her undersized

baking pan.

For additional reading on the

handing down of traditions check out Shirley Jackson’s short story The

Lottery.

Any given fly reel model

usually is available in a variety of sizes. Which size is right for you? The

reel needs to accommodate your fly line and approximately 50 yards of backing.

There needs to be a comfortable amount (1/2”?) of room between the fly line and

the line guard on the reel. If the line and backing leave very little room on

the reel you end up with an annoying problem while you are fishing. As fly line

is retrieved it tends to pile up on one portion of the spool. There is no

mechanism other than your finger to evenly distribute the line across the spool

as it comes in. If the spool shows little capacity remaining when the line and

backing are initially put on, the problem will be magnified on the stream. Your

choices at that point include reducing the amount of backing, replacing the

backing with a smaller diameter, lighter strength backing, or cutting off a

portion of the rear, non-tapered section of fly line.

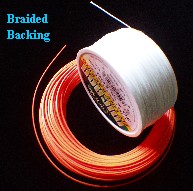

Another member of the fly fishing

insurance team is your fly line backing. You may not see your backing often but

when you do you will be glad it’s there when a memorable fish pulls all the fly

line from your reel and, then, wants more.

Choice of the right type

of backing is critical. Beginners ask me all the time if it’s okay to use

inexpensive monofilament spinning line for backing. Nope. Braided Dacron@ is

your best choice, for the following reasons: Choice of the right type

of backing is critical. Beginners ask me all the time if it’s okay to use

inexpensive monofilament spinning line for backing. Nope. Braided Dacron@ is

your best choice, for the following reasons:

1.

It does not stretch, unlike monofilament line. Backing that stretches

under the tension of fighting a big fish in heavy water and is subsequently

reeled onto the spool can exert a damaging force on the spool as the line seeks

to “relax” when the tension is removed. This problem will probably be minimal

for trout fishing, but can me a major one when playing salmon, steelhead and

larger saltwater species. I saw a reel spool filled with heavy monofilament as

backing actually damaged to the point of being unusable when an Alaskan salmon

was reeled in under great tension from a long distance.

2.

It is quite strong for its relatively small diameter. Because braided

Dacron@ takes up little room on the spool compared to a fly line, the angler can

minimize the size and accompanying weight of a larger reel.

3.

It does not readily deteriorate when exposed to the elements.

Monofilament exposed to sunlight weakens and deteriorates over time. Lubricants

and petroleum products from the fly reel that may come into contact with

monofilament may accelerate the process. Envision your monofilament backing

breaking as the fish of a lifetime swims away with your fly and fly line!

That’s why smart spin anglers replace the monofilament line on their spools

every year. I’ve had braided Dacron@ on some of my reels for more than 20 years

and it’s still in good shape.

Braided Dacron@ is

available in a range of strengths: 12 lb., 20 lb. and 30 lb. 20 lb. is the top

choice of most trout anglers. All are available in natural white, but some

brands are available in fluorescent green and fluorescent orange. It has been

my experience that the colored backings eventually bleed their colors onto the

fly line. This is not aesthetically acceptable to me, but if you like the

tie-dyed T shirt look on your fly line go for it.

Take Me to Your Leader

The transparent

terminal portion of your fly fishing system to which the fly is tied is the

leader. So as not to disturb the fish, the fly must be removed some distance

from the splash and shadow of a cast fly line. No matter that the fly line is

too large to fit through the hook eye of the average trout fly.

Early on I did not realize

that a leader is normally tapered, just as the fly line is. This enables the

casting momentum carried along the fly line to be transferred along the entire

length of the leader to extend the fly to the fish.

Though you can create your own

tapered leader tying together decreasing diameters of monofilament (or similar

modern material) line, it is easier to opt for knotless tapered leaders that are

extruded from a machine. Knots too often collect algae and vegetation in the

stream. It is irritating to be constantly cleaning the knots. If you fail to

do so, the leader may become evident to wary fish that may be alarmed by a

string of algae bits suspiciously hanging out in the vicinity of the fly. It’s

a little like spray painting the Invisible Man.

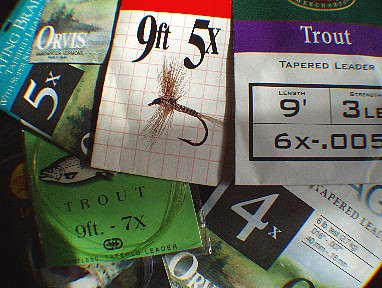

Leaders come in a variety of

lengths. The range runs from 3’ to 16’. Unless you have good reason to do

otherwise, select a 9’ leader. This length is suitable for most stream fishing

situations regardless of whether you are fishing nymphs, wet flies, or dry flies

with a floating fly line. The 9’ length is adequate for keeping the fly line

far enough removed from the fly so the fish are not spooked, but short enough

that the leader is easily coaxed to turn over, extending full length to present the

fly.

Here’s another fly fishing

vocabulary word: tippet. Often used incorrectly and interchangeably with

“leader”, the tippet is a very specific portion of the leader. It is the

non-tapered terminal portion of the leader to which the fly is tied.

When I spoke of the tapered leader I

failed to mention that it is not tapered over its entire length. The thick end

of a typical trout leader may measure 0.024” diameter. Over the next 6 ½’ to 7’

the taper smoothly scales down to a final diameter of, perhaps, 0.007”, for the

sake of example. Depending on the manufacturer, the final 20” to 30” of the

extruded tapered leader has a uniform diameter of 0.007”, the tippet.

Mathematically speaking, the tippet is a subset of the leader.

But I Hate Math!

I love math. I

taught secondary math. But even if you are not a numbers whiz, this is simple

math, and very important to your success. Nine-foot leaders have an array of

tippet diameters to choose from. That’s why I tried to emphasize that 0.007”

tippet diameter used previously was just an example. And, please note, I will

be writing about tippet diameters, not tippet strengths. You will find

out why later.

To cast and drift naturally, a fly

must be matched to a tippet of the appropriate diameter. If the diameter of the

tippet is too small relative to the size of the fly, the transfer of the cast’s

momentum may not pass along the entire length of the leader. The fly “load” is

too heavy or air-resistant. The leader collapses in a heap rather than

extending its full length during the cast.

If the tippet diameter is too large

for the fly you may not be able to get the tippet through the hook eye. To make

my point let’s pretend that we can get an oversized tippet through the eye and

the fly tied in place. There will be no problem with turning over the leader at

length. The problem arises as the fly drifts in the current. It will not look

natural. It will act like it’s attached to a stiff invisible cable. The fly

will not drift or swim naturally. This can seriously decrease your angling

success.

Tippet diameters have an unusual

designation. Rather than being commonly referred to by their measurable

diameter in inches, or feared and repulsive millimeters, they are referenced in

“X” numbers: 0X, 1X, 2X, and so on. This “X” number will be prominent when you

look on a leader package as you try to determine which leader to buy. With

minimal boring details here, suffice it to tell you that once upon a time

leaders were made from silkworm gut. Gut was fairly strong and lent itself to

being cut into successively smaller diameters if you had the right cutting

tool. If a strand of gut that measured 0.011” inches was trimmed down once ---

one time or “1X” --- the strand was reduced by 0.001” to the new, smaller

diameter of 0.010”. If the same strand was cut down a second time --- 2 times

or “2X” --- it was reduced an additional 0.001” to now measure 0.009”. cut down

a third time --- 3X --- the strand was now 0.008”. See the trend? I promised

you this would be simple math. I’ll put this info in table form and it will

reinforce the simplicity.

Tippet Diameter

“X” number diameter in inches

0X 0.011”

1X 0.010”

2X 0.009”

3X 0.008”

4X 0.007”

5X 0.006”

6X 0.005”

7X 0.004”

8X 0.003”

Note that there is an

“inverse relationship”. The larger the “X” number, the smaller the diameter.

The smaller the “X” number, the larger the diameter. The diameter of a 6X

tippet is smaller than the diameter of a 1X tippet.

The math lesson continues. All

this has led up to an equation that will help you determine the correct diameter

leader/tippet for any given size trout fly.

Fly hook

size

size 12

---------------- = “X” number Example

--------- = 4X

3

3

Not all hook sizes can be

divided evenly by 3, so approximate the best answer. For example, a size

16 fly would be best presented on a 5X leader. Both sizes 8 and 10 flies would

be best cast and fished on a 3X leader.

Leadership and the Economy

It’s going to

happen. Sooner than later you will break off a fly, and another, and another.

Trees, grass, submerged limbs and stream-bottom rocks. A wily fish may break

your leader. All these serve to shorten your leader. Changing flies of your

own volition cuts away at the leader. What one was once 9’ has been shortened

to 7’ or 8’. Your original tippet, or most of it, has disappeared.

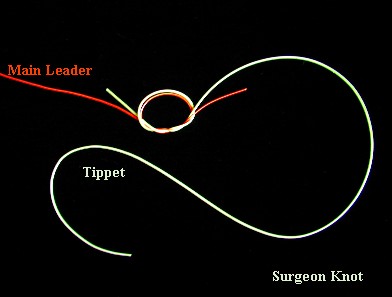

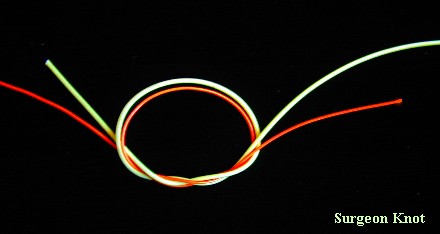

You have a couple of choices. One

is to replace your old leader with a new one. The cost will range from $3 to

$4. Your second choice is to extend the leader by using a surgeon’s knot to tie

a fresh section of tippet to the leader remnant. For the sake of economy, time

and versatility the second course makes excellent sense.

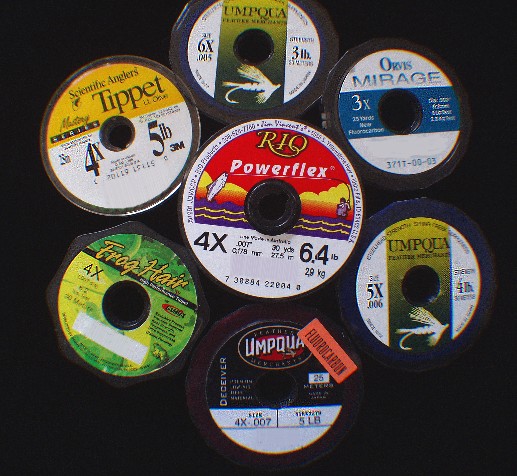

Tippet line comes on small put-em-in-your-pocket

spools. The best ones have a stretchy band covering the coiled line so it does

not unravel from the spool, presenting you with a pocketful of loose, tangled

mess. Carry a selection of diameters. Trout anglers will most often carry

spools of 3X, 4X, 5X, and 6X tippet. These diameters have proven most useful

for the trout fly sizes commonly used.

In addition to the leader already

tied to the fly line, it is wise to carry spare leaders. Until your personal

experience tells you otherwise, carry an extra 3X, 4X, 5X, and 6X nine-foot

leader. These will accommodate flies ranging from size 18 up to size 8.

If I change fly size must I always

change the tippet, too? It is reasonable in many cases to fish a tippet size

that is either ONE tippet size too large or too small than our mathematical

equation calls for. Personally, I am less concerned about fishing a tippet that

is one diameter too small for the hook size than I am about fishing a tippet

that is too large for the hook size. This is especially true in flat,

un-riffled water where a stream trout gets a good look at how my fly is drifting

with the current. A larger diameter tippet is a bit stiffer and adversely

affects the “swimability” of the artificial. In fact the trout in flat water

may be so wary that sometimes it may be mandatory for the angler to fish

a fly on a tippet that is one size smaller than the recommended ideal. If the

water is choppy, the fish’s vision is some what obscured. A slightly heavier

tippet probably has little affect.

Here’s another situation. Suppose

you are fishing a 3X tapered leader (this means that the tippet of the tapered

leader is 3X), and you wish to fish a size 18 fly. A size 18 hook is best

presented on a 6X tippet. So, is it reasonable to tie a section of 6X tippet to

the 3X tippet? I would not, for two reasons. The knot between two diameters of

such relatively big disparity may not hold secure. Secondly, the leader may

“hinge” or collapse at the knot. The 6X tippet may not lay out, collapsing in a

pile of little coils. The momentum of the cast has not transferred smoothly all

the way to the fly. The solution is to splice in 6” – 8” of 4X or 5X tippet

between the 3X and 6X. In my experience I can step the added tippet down one or

two diameters when splicing it to my leader, but not three or four jumps in

diameter difference. When splicing additional tippet to a leader, be cognizant

of the final leader length. In order not to create a leader that is too long

--- let’s say more than 10’ --- some (12” - 15”) of the 3X tippet on the

original leader may have to be cut back a bit before joining two more diameters

in this example. The section of tippet to which the fly is finally tied should

measure about 24”.

The hypothetical situations

continue. Suppose you are fishing a 6X leader (the tippet of the tapered leader

has a 6X diameter), and you want to tie on a size 12 fly. Does it make sense to

tie a new section of 4X tippet to the 6X? Usually not, because a collapsing

“hinge” may occur at the knot. Momentum is not transferred all the way to the

fly. It lands in a heap of 4X tippet. Better to, initially, cut off all of the

6X tippet and a little of the tapered leader behind it, then join the 4X

tippet. Ideally, you would cut the leader back to where the diameter was the

same --- or even slightly larger --- than the 4X tippet being added. Tie on

enough tippet to extend the leader to its original 9’ length.

A chemistry lesson

We’ve already had lessons in fly fishing

physics and math, and now it’s time for chemistry. Specifically, we are going

to discuss the chemistry of leaders and tippets.

There are three basic

materials from which leaders and tippets are commonly made: monofilament nylon,

co-polymer resin and PVDF (polyvinylidenfluoride), or simply “fluorocarbon”. At

first look all the materials appear the same, but using them as you fish

distinctions will become more obvious.

Monofilament nylon has

been in general use post WWII. Its relative “invisibility” compared to its

predecessors made it quite desirable. This was the leader material of choice

Furthermore, for making fly fishing leaders nylon monofilament could be extruded

from a machine in such away as to precisely control the creation of a smooth

taper. Monofilament was, and is, widely available and inexpensive.

In the early 1980’s a

new chemistry began to dominate the leader and tippet scene. Co-polymer resins

produced leaders and tippets that looked like monofilament but were up to 50%

stronger and suppler. An angler could use leaders/tippets of a smaller diameter

when desired, but give up nothing in breaking strength. Also, a supple tippet

enables a fly to drift more naturally in the current, with less of a hint that

the artificial was attached to anything. For these benefits the angler has to

pay 40% - 50% more at the cash register. Most think the cost well worth it.

Ten years later

“fluorocarbon” leaders and tippets became the rage for those willing to pony up

the price, generally 2 ½ to 3 times the cost of co-polymer items. For the same

diameter, co-polymers were stronger, but the fluorocarbon proved significantly

more abrasion-resistant. Alone, this does not warrant the price. But, by the

magic of chemistry, this new wonder material has a specific gravity greater than

that of water and a refractory index that causes it to “virtually disappear” in

water. The increased specific gravity enables the line to break the surface

film and sink, thereby not casting a shadow like monofilament or co-polymers

that tend to ride on the surface film. Fluorocarbon leaders and tippets are

more resistant to deterioration by UV (ultraviolet) light exposure, and do not

absorb water to the point of weakening and becoming more visible like some

co-polymers. At the turn of the new century, we are seeing fluorocarbon

chemistry improvements that have served to increase the breaking strength of the

material, too.

I can read your mind.

Is fluorocarbon worth the extra cost? Yes, with conditions. If the water is

very clear and the fish wary, fluorocarbon can be the difference between success

and failure. In clear lakes and ponds, for me there is no other choice. For

the budget route, cut the tippet off a standard co-polymer leader and replace it

with a fluorocarbon tippet. A carefully-tied, lubricated (with saliva)

surgeon’s knot allows for a secure splice of co-polymer material to

fluorocarbon, especially if the diameters are similar.

There should be a

warning label on each fluorocarbon leader package and tippet spool. “Warning!

The use of fluorocarbon can be habit-forming and hazardous to your pocketbook.”

We all have our little addictions. This is one of mine. Once you try

fluorocarbon leaders and tippets there may be no turning back . . . at least

until the next breakthrough in fly fishing chemistry.

Assembly Required

The ideal knot is simple, fast to tie, strong, and can be

tied without a tool. This narrows the field considerably. You need

to know three for fly fishing. You wannabe Knotmeisters can add more to your

repertoire. Tie your self silly, but start with these four, one of which you

may tie only once in a blue moon. This leads me into our astronomy lesson,

which may have little to do with fly fishing until you read my book on

fly fishing lakes, where the moon definitely seems to be important in your

fishing success.

A blue moon is a seldom

occurrence. With the exception of February, which really messes things up every

fourth year, there are 30 or 31 days in a month. A full moon usually occurs

once every 30 calendar days, but sometimes only 29 days. When a single calendar

month has two full moons in it, which doesn’t happen very often because of the

messy math, the second occurrence is referred to as a “blue moon”. Now, back to

the knots.

Here are the three ----

Tube / Nail knot --- used to tie braided backing to the rear of the fly line,

and

tie the leader to the front of the fly line.

Surgeon’s

knot --- used to splice more tippet to the leader.

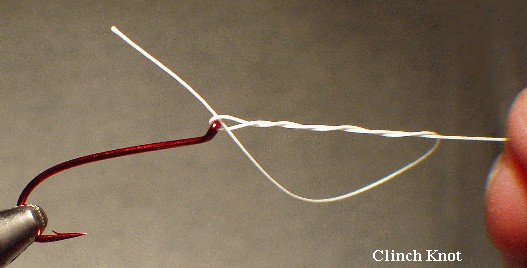

Clinch

knot --- used for tying the fly to the tippet.

Know that there are

alternatives and “improved versions” to all these knots. My goal is to keep it

simple. I want secure knots that I can tie in the field, no tools required.

Thus, my selection. Save fishing time and frustration by practicing these knots

with warm fingers at home under a bright light. There’s a little ditty to help

pass the time as you practice. It serves to reinforce the message.

Sing Along

Pretend you are gathered around an open fire with

your friends on a fly fishing trip. Get in the spirit of the moment, or have

another drink. This is sung to the tune of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”.

Know,

know, know your knots

Quickly

on the streams.

The more know the less you tie,

To catch the fish of your dreams.

(Second verse same as the first.)

Mr. Gorman has left the

building!

|