|

| |

You Must Know Your Quarry

Life Cycle, Spawning Migration, and

Physiology of Oncorynchus mykiss

by Michael Gorman (c) copyright 2006. All rights reserved.

As

a steelhead hunter, the more you know about your quarry, its life cycle and

behavior, the better your odds of catching one. When do they enter their home

rivers to spawn? Where exactly in the river will you find them? When do they

bite best? When do they not bite, and why? How keen are their senses? How do

environmental factors --- light, temperature, water clarity, flow changes, etc.

--- affect them? Generally, what are their likes and dislikes? How can you

effectively use this information to catch a fish?

A steelhead

angler is pursuing wary survivalists, fish so attuned to their environment they

were able to beat great odds to stay alive while the vast majority of their

comrades who began the journey together with them as fertilized eggs buried in

streambed gravel through adulthood over the next three, four, or five years met

their demise at some point along the way. These elite survivors, through their

individual instinct, strength, speed, reactions, awareness, stamina, and luck,

have evaded death from predators, hostile environments, dams, starvation,

pollution, disease, high seas fishing nets, and fishermen. Most are no

one’s fools who will grab the first baited hook, shiny lure, or pretty fly it

encounters. Even many of the oft-maligned hatchery-raised steelhead have

survived life’s trials to this point to successfully reach their stream of

release. Whether natives born in the river system, or those of hatchery

origin, all steelhead prove fabulous and worthy game for any angler pursuing

them. So, it is always with a sense of awe that I look at any steelhead

caught by me or my guests. Just like the fish, we have beaten the odds to

trick one into biting a fly. This fish has evaded death and capture for

years --- for its entire life --- to arrive at the single moment where you or I are fortunate enough to find

it on the end of our fishing line. An amazing encounter when you pause to think

about it.

A

steelhead (Oncorynchus mykiss), taxonomically classified with the Pacific

salmon, is an anadromous rainbow trout. An anadromous fish is one that

is born in freshwater, spends its adult life in saltwater, then, returns to

freshwater to spawn. By contrast, resident rainbow trout never leave

their freshwater homes. Being a resident or a migrant is largely due to genetic

inheritance. As a fish, if your parents were steelhead,

odds are great you, too, will find the ocean someday, too.

The timing of the steelhead

spawning migrations into the rivers and streams of western North America ---

their range spanning from central California north through Alaska --- vary

widely. Some rivers have one spawning run. Others have two. Some have both a

winter and summer; others, spring and fall runs. In addition to run-timing

variations, there is a wide spectrum life cycle minutia that will boggle anyone

trying to remember all the possibilities. “The life history of the steelhead

trout varies more than that of any other anadromous fish regarding the length of

time spent at sea, the length of time spent in freshwater, and the time of

emigration from and immigration to freshwater.” (Barnhart, R.A. 1986)

Rather than getting caught up in a morass of details about the

exact timings of spawning migrations, precise time ranges of actual spawning,

incubation durations for the developing steelhead eggs, freshwater duration for

the juveniles, and smolt migration, I am going to speak in generalities about

the “typical” Oregon steelhead, since Oregon is where I do most of my fishing

and guiding. Just know that tremendous variations of the steelhead life cycle

exist in its expansive geographical range. There are rebel steelhead outside

the main portion of the statistical Bell Curve in all stages of the “typical”

life cycle who will prove to be exceptions to my generalizations. I know this.

And, now, you know that I know this when you are tempted to cite

many exceptions to what I write in this chapter.

As

spawning time nears,

steelhead adults enter

tributaries of the main river they have ascended, or swim to the upper reaches

of the mainstem. Those entering tributariess tend to swim farther up than

chinook or coho salmon in order to find cool spawning areas with smaller-sized

gravel. Once the fry emerge from the gravel, they survive and thrive in cool

streams that have: “ 1) good streamside vegetative cover to keep the water cool

and provide plenty of leaf litter for growing the insects that steelhead eat and

2) lots of wood and boulders in the stream to create

riffle-pool complexes with plenty of places to hide and rest.” (Fitzpatrick

1999) In those tribs where the waters tend to recede and warm with the advance

of summer, the young steelhead drop into the main river.

In my part of the Pacific Northwest spawning is, typically, February through May. It is during this time frame

that a female steelhead will pair up with a worthy buck for the Dance of Life.

As spawning time nears the female steelhead selects a section of appropriate

graveled stream bottom where she excavates a nest, a depression, by

turning on her side and swishing her tail vigorously. A typical nest is one

to two feet across, and several inches to a foot deep. No more than a quarter

of the hen’s eggs are deposited in the nest. As the eggs are expelled from the

female, the buck releases sperm in a milky matrix which washes through the eggs,

hopefully fertilizing all.

Once her male suitor has fertilized

the crop, Ms. Steelhead moves upstream of the eggs and excavates another nest.

In a model of natural efficiency, as the hen creates the second nest she is

covering the first. The Dance continues as more nests are created, the eggs are

laid and fertilized, and the female steelhead is finally emptied of her precious

cargo. The collection of these four, five, or six nests is referred to as a

redd.

In his book, Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies, Trey

Combs suggests a twelve-pound female may lay 10,000 eggs. In general, adult

female steelhead contain about 2,000 eggs per kilogram of body weight. (Moyle

1976) One kilogram is approximately 2.2 lbs. So, about 2000 eggs per 2.2 lbs.

of body weight.

There is a species survival advantage

for not depositing all the eggs in a single nest. If any of the eggs go

unfertilized, a fungus can invade that egg, then, eventually, spread to destroy

the entire nest. Because they are physically isolated one from the other, the

fungus from an infected nest will usually not be able to spread to the next.

Having deposited her entire egg supply, the spent

female, now known as a kelt, is finished. She will eventually resume

feeding, rebuilding her strength, and make a move to the ocean again. Her life’s work for this year is complete once the last nest has been

covered. She will now go her own way and the mating partner, his. Unlike

the Pacific salmon which die soon after spawning, a spent steelhead can survive.

With a lot of luck these fish will return to this

stream next year to repeat this procreative drama.

The male, like his counterpart of the human species, complicates matters

for himself. He is capable of spawning with other females. Instead of being

satisfied with one successful mating encounter, the male now seeks out another

ripe female. Maybe he finds one; maybe he doesn’t. He may have to physically

fend off more potential suitors with the same plan. In addition to the

exhausting rigors of spawning, an embattled buck may be torn and wounded by

other would-be boyfriends. Between the wounds and physical exhaustion, the

buck may not be able to survive the return to the ocean. He may very well die

in the stream of his birth. There’s a lesson here somewhere for us all, guys

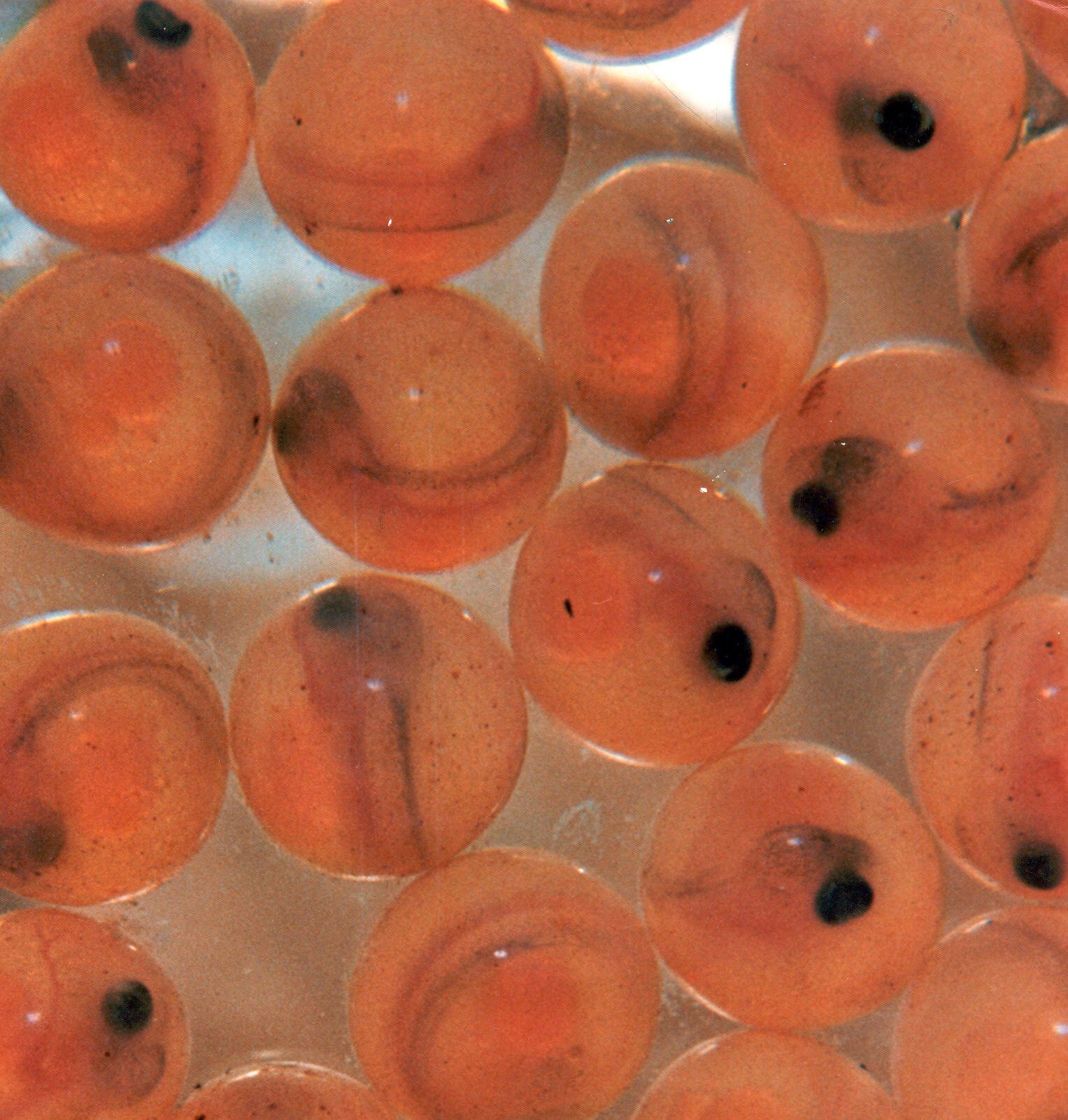

The

buried, fertilized eggs develop and undergo a metamorphosis over the next 2 – 3

months. Slowly, the egg starts to “morph” into a tiny fish. In several weeks

the egg has a small fish head and a small fish tail with a relatively huge belly

which is the shrinking egg. At this stage the developing steelhead is referred

to as an alevin. Having provided the infant steelhead with nourishment

up to this p oint,

the egg will eventually be entirely absorbed. The completion time for the final

absorption of the egg depends on water temperature, taking longer

in colder water. Then, the luckiest, most determined little steelhead will

wriggle, zig, and zag through the maze of interstitial spaces in the gravel to

make it into the wide open expanse of the stream. Here, they must now seek out

food items on their own to sustain themselves and grow. Most of

a survivor’s siblings may not make it, buried forever, never emerging from where

they were “hatched”. The tiny

survivor, then, must search for food, while at the same time not becoming a meal

for a larger predator. And, many more of his baby steelhead comrades who’ve

made it this far will not survive their first few weeks in open water, having

been eaten, starved, or swept to their deaths, unable to find shelter in raging

winter river flows. For those that do make it through their first year in the

river, many, again, will not see their second. oint,

the egg will eventually be entirely absorbed. The completion time for the final

absorption of the egg depends on water temperature, taking longer

in colder water. Then, the luckiest, most determined little steelhead will

wriggle, zig, and zag through the maze of interstitial spaces in the gravel to

make it into the wide open expanse of the stream. Here, they must now seek out

food items on their own to sustain themselves and grow. Most of

a survivor’s siblings may not make it, buried forever, never emerging from where

they were “hatched”. The tiny

survivor, then, must search for food, while at the same time not becoming a meal

for a larger predator. And, many more of his baby steelhead comrades who’ve

made it this far will not survive their first few weeks in open water, having

been eaten, starved, or swept to their deaths, unable to find shelter in raging

winter river flows. For those that do make it through their first year in the

river, many, again, will not see their second.

The cruel

sifting of natural selection continues. It is usually in the spring at age two

when most of our Pacific Northwest steelhead juveniles begin a journey

downstream that will eventually lead them to the Pacific Ocean. That is, of

course, if they survive future survival trials from dams, fishermen, more

predators, disease, injury, and potentially lethal high water temperatures.

Again, most of those that actually begin the trip toward saltwater won’t make it

in typical years.

Newly

emerged tiny steelhead swim freely, exploring their spacious, dangerous

environment. If their luck at surviving continues, the fry which beat the

odds will stay in their home stream here in the Pacific Northwest for one or two

years, attaining lengths of four to eight inches. In the spring,

responding to

their biological urge, on

the move, the young steelhead start migrating downstream, headed for

saltwater. For some in the lower portions of coastal streams, the journey is

short, maybe a few miles. Those in the heart of Idaho may have to traverse many

streams and rivers, journeying almost a thousand miles to reach the Pacific,

where most will stay to dine for one or two years. Some rare individuals, most often

from British Columbia, will remain in the marine environment for three or four

years.

Initially,

the tiny fry school in quiet protected portions of the stream, usually along its

periphery. Here they are sheltered from strong currents and predators as they

forage for food items. Their diet consists mostly of small aquatic insects, and

the occasional terrestrial. In the first weeks as free-swimming roamers,

the mortality rate can be very high, and largely determines the size of the

surviving class of a given river for that year.

As the steelhead grow larger over the next few months, the tendency to school

with its sibling disappears. Most juveniles strike out on their own for a more

solitary existence. With growth, physical features and markings on their bodies

become more evident. At this point they are commonly referred to as parr,

characterized by large, oval-shaped markings on the fishes’ sides. For the next

one to three years --- usually two --- the parr steelhead focuses on food and

survival. Driven by their inherited instincts, in the spring of their second

full year most steelhead smolt, beginning their downstream journey to the

ocean. The smolts, usually 4” - 8” long, just keep following and following the

flowing river maze until it reaches saltwater.

As the steelhead grow larger over the next few months, the tendency to school

with its sibling disappears. Most juveniles strike out on their own for a more

solitary existence. With growth, physical features and markings on their bodies

become more evident. At this point they are commonly referred to as parr,

characterized by large, oval-shaped markings on the fishes’ sides. For the next

one to three years --- usually two --- the parr steelhead focuses on food and

survival. Driven by their inherited instincts, in the spring of their second

full year most steelhead smolt, beginning their downstream journey to the

ocean. The smolts, usually 4” - 8” long, just keep following and following the

flowing river maze until it reaches saltwater.

Upon entering

the ocean, the journey in the salt is far from over. Our little Pacific

Northwest adventurers make their way hundreds, if not a thousand miles or more,

out into the Pacific Ocean to spend a year or, more typically, two, in the very

general vicinity of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Some British Columbia and

Alaskan fish may spend three or four years. Those migrants of extreme southern

Oregon, south of Cape Blanco, and those fish from California Rivers, stay much

nearer the coast in the Pacific. All have answered some instinctual and

environmental cues which take them to their marine stations. Here they feed,

they grow and they frolic until their genes prompt them to return to their home

stream as sexually mature adults.

Besides an

internal adjustment to its marine environment, an important exterior

physiological change has occurred as the steelhead heads to sea. The

body’s coloration is continuing to change for the sea-going rainbow trout when

entering the saltwater environment. The characteristic red lateral stripe

of its early freshwater life has faded to silver even before leaving freshwater,

as have the rosy hues of the gill covers. These changes progress,

until lost are the spots on its lower sides and belly. Instead the back is

charcoal with a hint of blue or olive. The sides become chrome bumper

silver. The belly is snow white. All these serve good adaptive

purpose: the fish is difficult to be seen by predators that would eat them.

Spied from above, the steelhead’s dark back blends with the dark ocean depths

against which it is viewed. The silvery sides of the fish reflect its

surroundings like a mirror. Eyed from below, the white belly helps

camouflage the fish against a bright sky backdrop. And,

consequently, such a fish is much more difficult for us two-legged predators to

spot a fresh-run steelhead when it enters the river than a fish which will, with

time, revert to its original rainbow trout colors.

After two

years (for most) of accelerated growth and the building of fat reserves, our

sojourners respond to their inner clocks, heading in the general direction of

their freshwater homes. Steelhead begin navigating toward their natal stream of

origin by, apparently, celestial and electromagnetic means. Iron-bearing

structures in some of the body’s cells orient the returning fish with an

indication of the magnetic North Pole to aid in its navigation. Once near the

coastline, the steelhead relies on its keen olfactory sense to pick up on the

trace elements “fingerprint” of its home stream. Like a bloodhound following

the trail, the fish locates the stream of its birth (or release, if of hatchery

origin), and the upstream ascent begins. The fish that started its epic travels

at four to eight inches tipping the scales at a few ounces, will return home

usually at 23” to 30”, weighing five to ten pounds, as determined by the

favorability of its ocean environment, the abundance of food, and its genetic

growth potential.

A few special

fish --- most from British Columbia rivers --- will grow extra large by

remaining in the marine environment for three or four years. It is ocean time

that produces the largest steelhead, some exceeding twenty-five, or even thirty,

pounds. The largest fly-caught steelhead weighed in at just over 33 pounds. It

was taken in B.C.‘s Kispiox River in 1965. The largest steelhead ever caught on

rod, reel and line was caught in saltwater off the coast of Bell Island, Alaska:

42 ½ pounds. It was inadvertently caught by a young boy trolling for salmon.

Some

Oregon rivers have runs of summer steelhead which enter freshwater May

through October, with a few rebels arriving earlier or later than this general

range. When is a summer-run actually a fall fish is open to interpretation.

Alaska and British Columbia have runs that are better defined as “fall” run

fish. And to confuse the issue further, in the Pacific Northwest we often see

an overlap of late-run winter steelhead with early-arriving summer steelhead;

ditto for late-run summer fish and early-run winter steelhead.

A summer steelhead arriving in its home river in May or June may

dawdle for 6 – 8 months before being smitten by the spawning urge. Amazingly,

the fish does not need to eat between the time it enters freshwater until after

mating. Their ocean-grown fat reserves are adequate. But, as steelhead anglers

will testify, you can induce the occasional steelhead to dine. It’s difficult

to ascribe this to any one reason. Perhaps we have triggered an automatic,

autonomic eating response. Think of being at a Sunday morning deluxe buffet.

Even though absolutely stuffed all of us can be prompted to partake of dessert

though we are not hungry. Lacking hands, a curious steelhead may examine

something tactilely with their mouths. They may strike or bite at something

which invades their personal space. These are a few possible explanations.

There may be others.

Steelhead may

return and successfully spawn annually several times before time, obstacles,

natural events or predators take their toll. A hardy British Columbia steelhead

hen was determined – through scale analysis --- to have returned to her home

stream for the sixth time.(Combs 1976) In most “normal” years the return rate

of would-be second-run returning adult steelhead is less than 10%.

I thought my IQ was at least average

Even though they have a

brain the size of a pea, as I recounted in the Introduction, it took me seven

years to catch my first steelhead. I was an excellent young trout fisherman

when I began my steelhead quest: skilled caster, athletic, determined, and

resourceful. However, I could not hook one of these elusive steelhead to save

my life. This was a bit odd to me since I often fished with other

less-experienced anglers who would occasionally land a steelhead as I stood

beside them. I even coached several rookies who had never fished steelhead

before, and they would sometimes hook a fish!

I have a guide friend ---

I’ll call him Glenn --- who maintains “steelhead are the stupidest fish that

swims”. Yeow! What does that say about my intelligence when I can’t catch one,

and I know they are in the rivers I’m fishing? Needless to say, I

protested Glenn’s remark to him. He invited me fishing.

We fished three different

rivers on three different days. He was the guide. I was the “client”. We used

his flies. I stood where he told me, and cast where he instructed. Moved when

he said “Move.” And changed flies at his command. Glenn fished

hard, too. Three rivers in three days. Prime time.

Fished with focus. Not a strike! Neither of us got a sniff from the “stupidest fish

that swims." I didn’t know which I felt more: amused or vindicated.

Despite their

minimal cranial capacity, those

steelhead which return to spawn are survivors: the fittest of the fit; the

wariest of the wary. In disagreement with my friend (we’ll still call him

Glenn), in a polite tone of course, I

reiterated that these returning voyagers are nobody’s idiots. We have fish, typically, in the 90

to 99th survival percentile who beat the odds, surviving a perilous

youth, scrounging for food, hiding from hungry bullies, fending off parasites

and disease, and dodging dam turbine blades. The vast, vast majority of their

siblings never even made it to the ocean, let alone survived all the saltwater

hazards to grow and thrive. These fish are extremely special when you consider

that only one or a few out of a hundred make it back to their rivers of birth to

challenge your fishing skills and wits. A steelhead is truly a worthy adversary.

Whereas much of our brain

mass can be devoted to “higher endeavors” such as creative thought, pondering

choices, and planning our next vacation, the fish’s little bit of grey matter is

totally focused on survival and procreation. A steelhead isn’t concerned about

finding the TV remote control or playing with his friends. It prime directive

is “What must I do to survive today?” If he or she cannot find the right

answers everyday, or runs into some bad luck, they are removed from the

gene pool. Just like the Marines looking for a few good men, Mother Nature is

constantly selecting only a few exceptional steelhead. All others will meet the

Grim Reaper.

Three of the fish’s senses

the astute angler must concern himself with are smell, sight and

movement/vibration detection. Let’s address these one at a time.

Smell

Once in the ballpark

vicinity of its stream of origin, a steelhead finds home base by discerning

through smell the unique ”scent” of its birthplace. The “scent” is very faint,

perhaps a few distinct molecules mixed with millions of others! The parking lot

oil on your wading shoes, the cat pee on your waders or the sunscreen

inadvertently rubbed from your hands to your fly may put off, even startle, a

willing fish. Always be thinking about what alarming underwater odors are

washing downstream to the fish below.

I was told many years ago

by an old, now-deceased, angling friend about L-serine, a natural

chemical found in human perspiration and natural body oils. He maintained this

is repugnant to fish. Subsequent internet research corroborates this. And

streamside observations of other anglers demonstrates the same belief that human

scent can be significantly repellant to steelhead.

The following was

discovered while surfing the internet. Some of it may be abbreviated and

paraphrased with reference to the author.

A chemical called

L-serine. The smell on your hands. I remember as a youth outfishing my father

and his angling cronies on almost every trip we made. It got so bad it was

embarrassing to my father's friends. Initially, Dad thought it was great. But

when his fishing buddies quit inviting us on their fishing trips, my father

suddenly found ways to avoid taking me along. At first I feared it had something

to do with body odor...or bad breath. I now believe it had more to do with the

odor on my hands (or lack thereof) than anything else.

Dad and I tried an

experiment some years later at a popular western Idaho trout lake. I baited

Dad's hook, he baited mine. He caught fish, I didn't. When we later baited our

own hooks, things returned to normal. I caught more fish than he did.

Technically, L-serine

falls into the category of compounds known as amino acids. The fact that amino

acids have a high solubility in water reinforces the problem, because fish thus

have the opportunity to detect this chemical.

While scientific studies

have not confirmed my "positive" L-serine theory, I strongly believe it does

exist. In his book, The Scientific Angler, author Paul C. Johnson writes,

"Every time a fisherman casts and retrieves his line and lure, he leaves an

invisible smell track. All humans have some level of L-serine in their skin oil;

everything a fisherman touches contains a chemical remnant of L-serine plus

anything else he may have had on his hands.

"What else?" Johnson

writes. "Plenty: gasoline and motor oil, suntan oil and sunscreen, bug

repellent, and nicotine, for smokers (my father was a heavy smoker), are all

potential negative smell track generators.

Johnson goes on to

describe the most common negative, neutral, and positive smell tracks. Every

angler would do well to memorize this list.

NEGATIVE SMELL TRACKS:

L-serine (human skin oil), nicotine, petroleum and derivatives (gasoline and

motor oil), suntan lotions, bug repellents, chemical plasticizers added to

soften plastics, and perfumed soaps.

NEUTRAL SMELL TRACKS:

Alcoholic beverages, anise oil, natural vegetation (grass, leaves), human urine,

chlorinated water and treated septic water, soda pop and fruit juices,

nonperfumed soap and biodegradable detergents.

POSITIVE SMELL TRACKS:

Fish extracts - including herring oil, baitfish guts, fish slime (can also be a

negative if the slime originates from a species offensive to the game fish being

sought; e.g., the slime of a northern pike is negative to many species), natural

bait (including juices from worms, frogs, crawdads, leeches and maggots), milk

and some dairy products such as cheese, and human saliva.

An old time walleye guide

described an experience he had observed on a top lake in Canada: Neither member

of a husband and wife team had even had a bite during a morning of fishing. They

went in for a shore lunch. Almost immediately when they went back out on the

water after eating, the wife started catching walleyes.

The husband, using an

identical line, lure, and technique, never got a strike. They began discussing

why. It was finally determined that the only thing they had done differently,

was she had smeared Oil of Olay on her face to prevent windburn. He tried

it...and began catching fish.

What's in the stuff? Among

other things, natural turtle oil.

For several years I've

been routinely washing my hands several times a day when I'm fishing; with a

good neutral (non-perfumed) biodegradable soap. Even if I "might" have a

positive L-serine on my hands, I'm still not about to take any chances.

~

Marv Taylor,

from “Smell Tracks” internet posting

I see a growing number of

steelhead and salmon guides who wear latex gloves all day. They do so since

they are constantly handling the baits and lures for their fishing clients.

They are moved to such an extreme convinced that scent matters, especially to

anadromous fish, survivors that have successfully navigated the last leg of

their journey home by their very sensitive noses. Apparently, latex

gloves are an effective barrier to human scent.

Wash Up Before Dinner . . . and Fishing, too

A fisheries biologist

friend of mine, Jay Nicholas, was the chief architect of The Oregon Plan,

a comprehensive living document of guidelines for improving the survival of

salmon and other anadromous fishes in Oregon. This plan was crafted in response

to the drastic decline of many native salmon stocks in Oregon. It was done at

the commission for then-governor John Kitzhaber.

Jay’s a smart guy and an

accomplished steelheader, so when he speaks I listen closely. He told me an

interesting story. It seems a steelhead guide acquaintance, skilled and

knowledgeable, had all of his clients wash their hands immediately before they

would begin fishing. This was done as son as they got on the boat so the

procedure could be overseen by the guide to make sure it was done properly. A

very specific, non-offensive soap had to be used. This guy was a fanatic, but

if it meant one more fish in the boat during the fishing day, that made for

happy clients who will return, and tell their friends, too.

I am a stickler about

sunscreen and insect repellent. These chemicals are often strong-smelling and

long-lasting: an extremely bad combo. For myself, I apply these at home or at

the motel and wash my hands thoroughly with soap before leaving. I apply

sunscreen or repellent to the back of my hands by placing a dollop on the back

of one hand and spreading it with the back of the other hand. If additional

applications are needed on-stream, I suggest taking a couple of minutes to

massage the hands with in-stream vegetation, mud and sand to mask the smell. I

will do the same to a contaminated fly or lure. It may be best to immediately

replace a “ruined” fly.

Whenever I suspect a fly

has a fish-repelling scent I will massage it in a mixture of stream mud, sand

and aquatic vegetation. If these are not readily available, I smear the fly

with the slimy algae coating of a river rock. Another scent that seems to have

a neutralizing, if not enhancing result, is to rub fish body slime on a fly. In

the natural course of handling and releasing a fish, slime adheres to my

fingers. Before I rinse them in the river I may rub my digits on a

possibly-tainted fly. It can’t hurt.

Also, I do not use fly

tying head cement on my subsurface steelhead flies. The nasty ingredients

contained in this liquid glue will clear your sinuses. I am sure they

will do the same for an offended steelhead.

Most of the time I have two

clients in my drift boat when I am guiding. When things are going according to

plan on trout fishing trips, both anglers are catching fish on a regular basis.

On a number of occasions over the years I have observed one angler’s number of

strikes drop to zero while his partner continues to catch fish as before. It’s

time to pull to the bank, “wash” hands, and change flies. Every time this has

happened the fishing success then resumes for both anglers. If resident

trout are this sensitive to repugnant scent you can safely assume that a

far-ranging steelhead that must find its home with its nose will be at least as

fickle.

A dry fly angler might

wonder about the scent put on a floating fly by some of the noxious floatants

used to waterproof a fly and retard its sinking. I use floatant regularly

myself. The reason the fish are not concerned is that they are in the

downstream “vapor trail” of the fly only for a brief instant as they rise to

intercept it. The fish are usually holding much deeper than the surface

currents that carry the smell over the heads of the fish.

Vision

Steelhead have great vision, so a stealthy

approach to exposed fish-holding areas is important. One of my favorite games,

particularly in small coastal streams in the winter, is to cast to visible

fish. Experience has taught me to wear a camouflage jacket, stay low, stay

behind the target and cast sidearm. Once I am spotted, even if the

fish doesn’t

immediately dart for cover, the game is over. fish doesn’t

immediately dart for cover, the game is over.

A fish in shallow water, or holding high in the

water column, has a greater scope of the surroundings above the water line, a

larger cone of vision for things external to the water. A stealthy

approach is

demanded of the angler to accommodate this. Crouching or kneeling positioning,

minimal movement, clothing colors that blend with the surroundings, and sidearm

casting may all be essential. Remembering that fish face into the current, the

fisherman should move toward his position from downstream of his quarry.

Jackets, tops and shirts which are red, yellow,

or white cause me to wonder about possibly discouraging a steelhead to bite.

These are hi-vis colors that may draw attention to an angler, resulting in

startling or, at least, alarming a steelhead. Though a red garment makes for

eye-catching photos, I request that my clients avoid this color, and the others,

too. A red cap will provide enough pizzazz. Though I’ve had clients wearing

bright clothing catch steelhead, I always

recommend colors that blend with the

dominant background are my suggestions. An angler wearing my taboo colors may

catch three steelhead, but I wonder if he could have hooked one or two more by

sporting sporting neutral tones.

Vibration

The lateral line is

a sensory organ that runs along the side of a fish, and act as sensitive

“ears”. It detects vibrations and movement. Vibrations may convey “food”,

“enemy”, “unknown, but probably dangerous”. The lateral line is also

particularly temperature sensitive. It prompts the steelhead toward water

temperatures that are nearer its preferred range of 50 to lower 60’s degrees

Fahrenheit.

Careless, noisy wading, or

banging around in an aluminum drift boat will announce to the steelhead your

arrival. Because water is a denser medium that air, underwater sound carries

much farther, and the volume does not diminish with distance as rapidly. Wary

steelhead will go to High Alert. A fish in an alarmed state is not likely to

bite your fly.

The keen senses of survivor

steelhead should cause you to wonder. They certainly plant questions in my

mind. During the seven years I struggled to catch my first one I wonder how

often I blew opportunities due to my lack of knowledge about the sharp acuity of

a steelhead’s senses of sight, smell, and “hearing”. Even today as a long-time

fishing guide I wonder how many more fish my steelhead clients could have /

should have caught but did not due to being detected as we set up to fish a

particular piece of water. I will never know, but I do, now, have awareness.

It’s actually a bit

unsettling to consider how many steelhead are startled out of a biting mood

because insufficient homage is paid to their sharp senses. Their importance can

easily be discounted by anglers --- me included --- when a few steelhead are

hooked and landed during the fishing day. We can be lulled / trapped into

believing our stealth and scent precautions are adequate. Personally, my day is

made when I or my clients catch a few steelhead. We may have hooked three, but

could we have hooked six if we had accorded greater respect to ability of

steelhead to detect and be put off by our presence. Maximum fishing

effectiveness starts with awareness. I am convinced I can never be too careful

about human or repugnant scents, visual detection, and fish-scaring noise as I

wade or move around in my boat.

There

are three factors that, in large part, determine the eventual length and weight

of a steelhead: the abundance of marine food items (primarily small fish and

crustaceans), the length of time spent in the marine environment, and its individual genetic

potential. With rare exception, the law dictates that native

steelhead must be released. Or, you may choose to release hatchery fish,

too. You might be curious about how much a released fish weighs.

Since very few anglers carry an appropriate scales with them, a couple of key

measurements will help you estimate the steelhead's weight,

Estimating a steelhead’s weight

There are a couple of

equivalent mathematical equations for determining a steelhead’s weight in

pounds. You need two measurements in inches: the length and the maximum girth.

The later is best taken so the measuring tape is touches the leading edge of the

dorsal fin as it is carefully wrapped around the fish. And because the girth

has such a great bearing on the final answer (it’s squared), be accurate to the

fraction of an inch.

If you are not carrying a

cloth or soft plastic tape measure, use a section of leader material to make the

measurements. Cut them as the measurement is made. Accurately measure these

pieces of cut line at your convenience.

Steelhead size estimation: 0.00133

x length in inches x girth squared = approximate pounds. Mathematically

this equation is the equivalent of (l x g2) / 750 = approximate pounds

For a cruder but quicker

estimation for fish from 24 to 35 inches, subtract 20 from the length. The

remainder is approximate weight in pounds. Example: 27” length – 20 =

about 7 pounds

Steelhead Activity & Behavior and Water Temperature

Let me make another

generalization here for simplicity. Summer steelhead are more active, more

aggressive, than those of winter. It has to do with water temperature. Fish

are cold-blooded creatures. Their body temperature assumes that of its

environment. Given a choice steelhead will choose water that measures, roughly,

between 50 and 60 Fahrenheit. This is a very common range in our NW streams

June through October. Late November through April, upper 30’s to mid 40’s

predominate.

With some exceptions, I must put my fly right on

the nose of a winter steelhead to interest it. Numerous sight fishing

opportunities over the years tell me this is so. Six inches from an interested

steelhead may be too far for the fly to entice it.

As an aside, since I have

made a specific reference here, again, to fly fishing, let it be known

this is my preferred angling method. I have caught scores of steelhead on

assorted baits, spoons, spinners and diving plugs, but I enjoy the challenges

presented by fishing the fly. Not everyone is willing to do that. I like this

fact, especially in fly-fishing-only waters. Not everyone can catch a steelhead

on a fly, especially in the winter. I like that, too.

Fly fishing for aggressive

summer steelhead offers satisfying thrills that cannot be found with any of the

other methods. The hard grab of a wet fly presented on a tight line downstream

gives you the sensation of being unexpectedly struck by lightning, only in a

euphoric, not a hair-raisingly painful, sense. Or, watching the big head of a

rising steelhead pierce the surface as it intercepts a skating dry fly has no

freshwater parallel. I always recommend that my students and clients have their

hearts checked by a cardiologist before trying this. This scene CAN stop your

heart! Every time I bear witness I still can’t believe what I am seeing. Talk

about addictive.

Summer steelhead will chase

a fly. They will track it across the current. They will swim to the surface

from six feet deep to eat a fly sometimes. However, much of the time these fish

will not budge, no matter the fly, the presentation, or the depth. Lockjaw.

Bad attitude. Like a stubborn five-year old at the dinner table.

This segues into my next

point: migrating steelhead do not need to eat. They are healthy and active

living on the fat supply created in the ocean. A steelhead entering a stream in

June has the health and energy to forgo food until after spawning in January,

February or March the following calendar year. The spawned-out kelt will

then start looking to dine. As they re-coup and make their way towards the sea

again, feeding habits and diet will closely approximate those of the resident

trout in the river.

So, why will a fish that

does not need to eat bite a fly, chase a lure or swallow a bait? I like to use

an analogy here. Imagine yourself at your last Sunday brunch at a fine

restaurant. Odds are good you ate too much. The food was excellent and you

wanted to make sure you got your moneys worth. Maybe even a little more than

your money’s worth. When you know a single bite more will make you burst

(visions from a scene in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life), you spy

this fudge cheesecake with cherry-cream topping creation. You shouldn’t. You

must. You will. I’m sure steelhead occasionally do the same thing. Lucky for

us.

A Guide Story – How Low Can You Go?

As I remarked earlier, steelhead have great

vision. One of my favorite games, particularly in small coastal streams in the

winter, is to cast to visible fish. Experience has taught me to wear a

camouflage jacket, stay low, stay behind the target and cast sidearm. Once I am

spotted, even if the fish doesn’t immediately dart for cover, the game is over.

My buddy Phil was desperate to catch a winter

steelhead on a fly. This prompted a little adventure on Oregon’s North Coast.

We went to a favorite small stream in January during a cold snap during which it

had not rained for more than a week. Low, clear water and spooky fish are what

I expected and, indeed, these are what we got.

There are advantages and disadvantages to low

water. The opportunity to visually locate and cast to holding steelhead is a

tremendous plus when the stream is a trickle. Additionally, there are fewer

prime holding areas for the steelhead to station themselves. These holding

spots are more obvious, more defined at reduced flows, which translates into an

easier time locating the fish. At lower water most, if not all, of the prime

holding lies can be approached by a determined hunter in chest waders. Such

wading apparel also allows access to both sides of the river when your course is

steered by dense brush, high sheer banks, and private property.

There are a couple major disadvantages to reduced

river levels. Steelhead that have beaten tremendous odds to have survived the

perils of youth in freshwater and predation and attendant hazards of the marine

environment have very keen senses: sight, “hearing”, and smell. Extreme stealth

is required to be a successful fly angler here. Slow, quiet movements and a low

profile are key. Stand too high or wave your rod tip overhead and you will be

seen. Shuffle the stones or stumble while you approach, you will be detected.

Once alerted, though you may still be able to watch a holding steelhead, they

will refuse to bite.

When Phil and I stalked our way up the river we

were careful to move slowly and quietly. (You do want to move upstream because

fish face into the current.) As we came upon a likely tailout I spied

three fish finning ever so slightly to maintain their exposed, but undisturbed,

positions. As Phil moved up beside me the trio darted towards deeper water near

the head of the pool upstream.

With Phil remaining stationary for the time being

I circled away from the water in order to approach their suspected position from

the side while keeping an extremely low profile. In fact, I approached on my

hands and knees to the elevated gravel bank overlooking the pool. This would

have been an interesting scene to a wandering observer who happened by. My

stealth was rewarded. I managed to see the three fish now huddled in faster,

deeper water. This would actually be a better holding area for Phil to approach

when he prepared to cast to our quarry.

It is important to let the fish settle in and

settle down once they have been alarmed. Initially they will not bite. Time

must pass for them to shake their worries. In the meantime I had Phil retrace

my circuitous path so that he could see his eventual targets. He actually

one-upped me in the stealth department: he slithered on his belly as he moved

onto the high gravel bank. Then, like a dog smelling a pheasant goes on point,

he elevated to all fours, studying the pool from his hands and knees until he

spotted the steelhead.

Once he had backed quietly from his poolside

position, Phil rejoined me at the tailout, well out of view of the fish. We

double checked his terminal gear. The leader and fly were as they should be.

No nick in the line, and the hook point was sharp. I had tied on a baby pink

Glo Bug bearing a fluorescent green dot in its center. It was this very same

pattern that enticed my very first winter steelhead.

Under my direction Phil made his approach to

fishing position. Crouched, with a snail-like pace, Phil moved upstream along

the river’s edge, barely getting his boots wet in ankle deep water. Once he got

with in reasonable casting range --- 25 – 30 feet --- it was time for the dance

to begin. Keeping the rod tip low, casting sidearm, Phil was instructed to make

the first cast too short. He was a dutiful student. The idea here is to

prevent the possibility that the angler will cast farther than he realizes,

alarming the fish as the line splashes on or above their position. The game

would be over before it had begun.

There is also the chance that even a cast that is

way too short could draw the attention of one of the fish to the fly even though

it had landed well behind it. Do not underestimate the vision and crazy

behavior of a rebel steelhead.

Of the trio of steelhead sighted, the fastest and

most determined was, also, the smallest. This chrome rocket charged the egg fly

on the first cast. In a blink it made an aggressive interception, virtually

hooking itself. Phil did an adequate job of playing the steelhead and

eventually brought it to hand. My friend had his first steelhead and a lifetime

memory.

Though

I have personally landed many hundreds of steelhead, I consider myself fortunate

each time I put another

one in the net or slide it into the shoreline shallows. I’ve overcome the odds

again, having fooled a fish that has successfully dodged danger and demise every

day of its life to eventually find my fly. Amazing!

Something is

wrong with you if you do not feel a little reverence when you hold a captured

steelhead in your hands, even if you will, in a few moments, “dispatch” the fish

for the home BBQ. If you ponder, even briefly, what this fish has gone through

to return to the exact point where your paths have crossed, and it grabbed your

hook, you can't help but be a little bit wonder-struck. The steelhead has

unknowingly timed its life efforts for this eventual encounter with you, perhaps

its final rendezvous with its destiny. This fish has cheated death for

years, facing and overcoming life-threatening challenges every day of its life

until you caught it. The steelhead can be both food . . . and "food

for thought".

Michael Gorman (c) copyright

2006. All rights reserved.

References

1. Combs, Trey, Steelhead

Fly Fishing and Flies, Amato Publications, 1976

2. Moyle, P.B., 1976, Inland

Fishes of California, University of California Press, Berkley, p. 405.

3.

Barnhart, R.A. 1986. Species profiles: 1ife histories and environmental

requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (Pacific Southwest --

steelhead. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 82(11.60). U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers, TR EL-82-4.

http://www.nwrc.usgs.gov/wdb/pub/species_profiles/82_11-060.pdf

4.

Fitzpatrick, Martin, Coastal Steelhead Trout: Life in the Watershed,

Cooper Publishing, 1999.

5. Marv Taylor, from “Smell

Tracks” internet posting

|